First the waters came with the rains of Hurricane Irene’s remnants, swamping dozens of Vermont communities, destroying homes, businesses, roads and upending lives.

Now, five months later, the stories are coming. There are stories of people who waded through the flood to save themselves, their pets or at least some of their possessions, whose lives were thrown into chaos. Many are still involved in the long-term process of rebuilding those homes and communities, not to mention their lives.

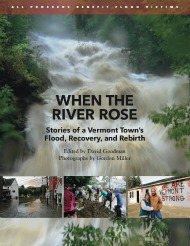

In Waterbury, where Irene’s fast-rising waters forced many to wade from their homes and damaged a third of the village’s buildings, a group of residents have contributed to a book called “When the River Rose,” part community memoir, part personal catharsis and part recovery fundraising tool.

“It’s an opportunity to reflect on what’s happened and move forward, and I think that’s an important part of restoring community connections so others know what you’ve been through,” said Waterbury author and journalist David Goodman, who edited the soft-cover book. “If no one knows your story, you’re constantly left to repeat it. It enables us to say, `This is our story. Let us show you and tell you.”‘

The Waterbury book is one of the books, videos and oral history projects that have been or are being produced from one end of Vermont to the other to record the experiences of thousands of people who lived through the flood.

In addition to the books and videos, scores, if not hundreds, of people have told their stories in small groups organized by the Vermont Folklife Center, the Middlebury organization dedicated to presenting the folk arts and cultural traditions of Vermont.

The Waterbury book includes the story of a state trooper who had to rush home to Waterbury from a detail where she had been prepared to evacuate Vermonters threatened by a weakening dam. Arriving home, she waded through chest-deep waters to save her two dogs, kept in kennels on the first floor of her flooded apartment.

“My apartment door opened under intense pressure and was difficult to open. As I opened it, more water rushed in. I ran through knee-deep water past my floating couches to find my dogs up to their necks.” She did save her dogs.

In Bethel, a group of seventh-graders shared their stories in a separate memoir titled “Grab your Toothbrush and a Flashlight! We’re headed to the Neighbors!” The book has sold well enough for the kids to make a donation to the town select board to help pay for ongoing recovery.

“Some of the stories are tough, tough to tell, tough to hear, but, you know (with) everyone sitting together, there is a real sense of community in the telling and a lot of support, to a session. When we arrive at the end, there is a tremendous feeling of uplift of strength and resiliency,” said Gregory Sharrow, the Folklife Center’s education director who has been involved in the circles, which will become part of the center’s archives.

In recent years, professional historians and grass roots organizations have been collecting stories of traumatic events across the country, be it the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans or the series of tornadoes that have hit the central part of the U.S., said Mary Larson, the president of the Oral History Association and the head of the Oklahoma Oral History Research Program at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater.

“If all of these narratives are getting generated, it would be nice if there were some kind of a public repository for them,” Larson said.

At least one of the areas devastated by tornadoes last year is trying to build a museum or library that can become a repository for the stories told after the tornado that hit the community last May, she said.

“It may or may not technically be oral history, but it doesn’t mean it’s not a valid way of collecting information,” Larson said.

Back in Vermont, the warnings were issued before the remnants of Hurricane Irene hit the state on Aug. 28, but few people expected the flooding would rival the state’s epic flood of 1927, by far Vermont’s greatest natural disaster. Like the’27 flood, normally placid rivers swept into low-lying towns, killing six. It swept homes from their foundations or flooded their first floors, destroyed roads and bridges and cut some communities off from the outside world for days.

The stories being collected in Waterbury, Bethel and elsewhere focus on the disaster at a personal level.

Back in Waterbury, Goodman said he started collecting stories during the cleanup, only hours after the Winooski River had receded into its banks.

“I very quickly found that while I was good with a shovel, I was better with a pen. What I do is tell stories,” Goodman said. “When I came back the next day and had my notepad, I found people exhausted and shell-shocked, but they had a lot to say.”

They become more than just stories of wading through the water. The stories tell of how the flood forced people to empty their houses to dry things out and so they could begin repairs. The process also bared their souls to strangers who came into their homes to help clean. Others became friends with the neighbors they never knew.

“The words began pouring out of them,” Goodman said. “It was the feeling of someone sick in the hospital. You lose all modesty. Your whole life is on the front lawn.”

Topics Flood

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Trump Demands $1 Billion From Harvard as Prolonged Standoff Appears to Deepen

Trump Demands $1 Billion From Harvard as Prolonged Standoff Appears to Deepen  Allstate CEO Wilson Takes on Affordability Issue During Earnings Call

Allstate CEO Wilson Takes on Affordability Issue During Earnings Call  US Appeals Court Rejects Challenge to Trump’s Efforts to Ban DEI

US Appeals Court Rejects Challenge to Trump’s Efforts to Ban DEI  Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance

Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance