Britain’s push to become a “space superpower” is being undermined by political disarray and weak domestic investment, while showing how the nation needs international partners more than ever post-Brexit.

In a case study of UK industrial strategy after leaving the European Union, Britain is embracing collaboration and mergers, while targeting niche roles in the booming space economy like curbing space junk and launching small rockets, instead of large-scale ownership or leadership, top-ranking officials and executives told Bloomberg News.

The US’s close strategic ally is settling for the supporting role at a time of geopolitical turmoil and economic headwinds. In 2023, Britain’s top satellite operators — Inmarsat Group Holdings Ltd. and OneWeb Global Ltd. — were absorbed by overseas rivals who are bulking up against Elon Musk’s fast-growing Starlink, while launch projects have been sidelined by bankruptcy or delays. German startup HyImpulse Technologies GmbH delayed plans for a launch from a new Scottish spaceport last year after slow progress there led the firm to seek alternative sites, Chief Executive Officer Mario Kobald said in an interview.

Meanwhile, Brexit has hurt recruitment and severed Britain’s access to Europe’s critical positioning satellites, increasing risks to its post-COVID economy.

“It would be a skills challenge anyway without Brexit, it’s just a more acute skills challenge because of Brexit,” said Lucy Edge, chief operating officer of the Satellite Applications Catapult, a government-backed incubator.

Britain’s political class is trying to cultivate its £17.5 billion ($22.3 billion) space industry, leveraging its historically strong financial sector and regulators — but that’s undercut by a revolving door which sees ministers struggle to remain in post.

To be sure, the sector is growing as part of a global wave of space investment, and conflicts around the world have boosted defense spending. UK companies are also bulking up, underscored by London-based BAE Systems Plc’s $5.6 billion acquisition of Ball Aerospace in August.

“Space is so interlinked and also so big and expensive, unless you’re the US it’s very hard to have the full range of capabilities, in one medium-sized nation state,” David Willetts, chair of the UK Space Agency’s board, said in an interview. “But what you can do is have particular strengths which make you so valuable that other people want to work with you.”

Martin Sweeting, founder of Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd., which previously counted Musk as an investor, said the government’s oft-repeated goal of the UK becoming a space superpower is “fatuous” given its spending. He noted that leaving the EU meant firms like his couldn’t continue work on lucrative contracts for the bloc’s satellite-navigation program Galileo.”Brexit just killed that stone dead,” Sweeting said.

Political Upheaval

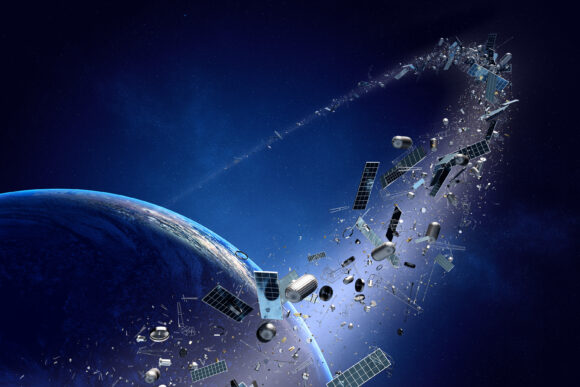

As the global industry becomes more commercial and less dominated by governments, former space minister George Freeman said Britain’s “biggest lever” is setting and enforcing sustainability standards to curb the proliferation of space debris, as risks grow with thousands of new satellites flung into orbit.

Such criteria, outlined last year, would reward responsible space programs with access to financing and insurance, backed by institutions like 336-year-old insurance market Lloyd’s of London Ltd. The push even enjoys royal support, with King Charles III introducing a space sustainability seal drawn up by iPhone designer Jony Ive at Buckingham Palace in June.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s tactic of using his country’s great power legacy to stay relevant in new technologies follows his November summit at WWII code-breaking base Bletchley Park, aimed at positioning the UK as a hub for artificial intelligence.

But as Sunak prepares for an election after more than a decade of Conservative Party rule, the space sector shows a hot-and-cold approach to industrial strategy, with decisions waylaid by frequent changes in administration. For instance, Sunak recently revived the National Space Council, which Boris Johnson founded in 2020 with rhetoric of turning post-Brexit “Global Britain” into “Galactic Britain” and was subsequently scrapped by Liz Truss during her brief stint as prime minister.

“After 13 years under a Tory merry-go-round of ministers and policies, the one thing businesses and investors in all sectors keep telling us is that they want stability,” Labour’s representative for space, Chi Onwurah, said by email.

Britain’s space sector has more than doubled in size since 2010, according to a government spokesperson. “The UK sees more private space investment than any other country in Europe,” the spokesperson said.

GPS ‘Crisis Plan’

After its Brexit exclusion from EU systems, Britain is now “critically dependent upon” the US-owned GPS navigation system, Andy Proctor, a former UK official and specialist in positioning, navigation and timing, said in a 2022 submission to Parliament. Proctor described increasing risk given “electronic warfare systems being used in Europe today.”

British officials will now “develop a crisis plan” in case such services become unavailable and critical systems go offline. State-commissioned research in October showed losing access to satellite navigation systems would cost the economy more than £1 billion a day.

Satellite Slump

Counter to the Brexit motto “take back control,” some UK champions are being pulled into overseas conglomerates.

In May, California-based Viasat Inc. bought the UK’s largest satellite operator Inmarsat. While it has committed to keep operations in the UK for five years, Viasat has lost half of its value since the deal was announced in 2021 and last quarter announced it would cut 10% of its workforce globally.

French state-backed Eutelsat Communications SA merged with OneWeb in September. While the deal split ownership equally, the group is headquartered in Paris and France holds a bigger stake than the UK government.

British space manufacturing is already dominated by overseas firms like aerospace giant Airbus SE. 80% of the UK Space Agency’s spending is pooled in the European Space Agency — a non-EU institution — a proportion which hasn’t changed since Brexit, although a UK government spokesperson said the country’s long-term plan for ESA participation is under review. This month Britain rejoins the EU’s satellite earth observation program Copernicus, after leaving due to Brexit.

Some startups are funded by bullish British investors like Seraphim Space. Since Seraphim listed its investment trust in London in 2021, the share price has fallen by two-thirds, which the company blames on inflation and interest rates. Challenges to the city’s capital markets have prompted tech firms like Arm Holdings Plc to seek funding in New York instead.

Seraphim’s Chief Investment Officer James Bruegger praised the UK’s approach, such as its space strategy, but warned of a “looming risk of falling behind without increased financial support to drive high potential company growth” in an emailed statement.

“The great challenge is — in this race for the global commercial space sector — scale of operation, scale of finance,” Freeman, the former space minister, said in an interview at an October London Stock Exchange space event. “You’re global and integrated, or you’re nothing.”

As part of its surprise $500 million OneWeb investment in 2020, the UK secured a “golden share,” giving it national security rights and a preference to site launches and manufacturing on a commercial basis in the UK. The arrangement heralded big supply and rocket contracts when OneWeb upgrades its fleet with a so-called ‘Gen 2’ system later this decade. But to satisfy EU demands, Eutelsat could work around the British share for a planned €6 billion EU satellite system called IRIS2, aimed at rivaling Musk’s Starlink.

Eutelsat CEO Eva Berneke told investors in May it could “have a part of the Gen 2 of OneWeb outside the so-called golden share of the UK” if a customer such as the EU requires it.

When the Eutelsat-OneWeb deal was announced, Freeman warned the deal could “hand over another key industrial asset to UK competitors.”

Two months after it closed, in another chapter of the political churn impeding the UK’s cosmic ambitions, Freeman stepped down as space minister.

Topics Europe

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market

What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market  Trump’s Repeal of Climate Rule Opens a ‘New Front’ for Litigation

Trump’s Repeal of Climate Rule Opens a ‘New Front’ for Litigation  Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears

Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears  Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance

Insurify Starts App With ChatGPT to Allow Consumers to Shop for Insurance