Jargon often gets in the way of clearly understanding the climate challenge. While some technical terms such as “net zero” are useful and continue to gain wider acceptance, others aren’t so helpful. Take the phrase “hard to abate.”

The simplest definition of “hard to abate” is that an industry finds it difficult to lower its greenhouse gas emissions. The industries that the term is typically used for are steel, cement, chemicals, shipping, aviation and sometimes long-distance trucking.

Yet “difficult” can be interpreted in different ways. It could mean these industrial sectors don’t have the technology to cut emissions. Or it could mean the technologies are so expensive that it will render their product unprofitable. Or it could mean, given the lack of regulations, these sectors find it hard to justify the effort needed to reduce emissions.

Companies ‘Paralyzed’ as Australia Plans Tough Climate Rules

The many meanings of “hard to abate” is why experts say there is a good argument to stop using it. “Industry has adopted the phrase as a way of not wanting to take action,” says Claire Curry, head of technology, industry and innovation at BloombergNEF.

So far, most progress on reducing emissions has come from building out renewables and moving to electric vehicles, which covers electricity and transport sectors. That’s a fair place to start, given a key way to tackle the climate problem is to electrify as much as possible and produce electricity without the carbon impact. And electrifying industrial processes or shipping and aviation is a bigger challenge than electrifying road transport.

But if “hard to abate” means those sectors don’t have the technologies to reduce emissions, that’s a tough one to back up. Emissions from steel, cement and chemicals can be cut using carbon capture technology, which can work well at scale. That’s before even looking at other technologies, such as using only renewable electricity to make steel from iron ore (through electrolysis), or replacing limestone with carbon-free raw materials to make cement, or deploying green hydrogen to making chemicals.

Meanwhile, any arguments that suggest these abatement technologies are too expensive create a good reason to push for more investment in research, additional policy support to reduce the green premium, or securing deals with established companies that can help bring costs down sector-wide. Take the example of H2 Green Steel: The startup has raised billions of dollars partly because it early on secured contracts for advance purchases from big companies such as Mercedes-Benz and Ingka Group.

Michael Liebreich, chief executive officer of Liebreich Associates and managing partner of EcoPragma Capital, is more blunt. “There are no longer any so-called hard-to-abate sectors,” he wrote for BloombergNEF earlier this year. “There are only some sectors in which clean solutions are not projected to undercut their fossil-based alternatives, perhaps ever. They will require a carbon price, but it’s an affordable carbon price: one that we are wealthy enough to pay, should we so decide.”

Liebreich told me in an interview that it’s better to use the phrase “affordable to abate” instead. That is to say, it’s not “free to abate,” because there’s a cost to deploying these low-carbon technologies and some of which may never become cheaper than fossil-fuel alternatives. But the cost is increasingly becoming more affordable, especially when compared to the cost society will face by not acting on climate change.

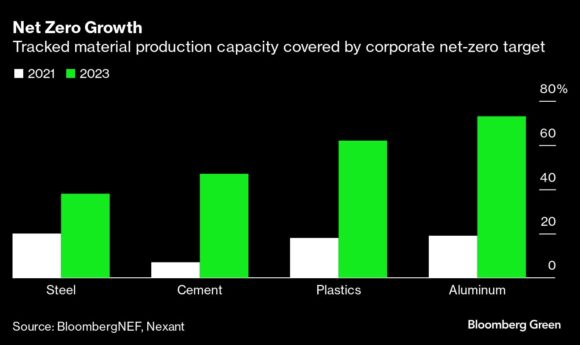

It’s why Curry doesn’t use “hard to abate” in any of her reports for BloombergNEF. It isn’t to minimize the challenge or the effort that needs to be put in these industrial sectors. But it is to acknowledge that there are now technologies to address the emissions and proven policy tools that can help scale up these technologies. That understanding is starting to show in the net-zero commitments from not just countries, but also companies in many industrial sectors.

Until 2018, there were no big companies or countries with net-zero goals. Now, most major companies (including from hard-to-abate sectors) and countries have a net-zero target, meaning there’s no escaping that all emissions need to be reduced. “Saying something’s too hard becomes a really transgressive act,” said Liebreich.

Akshat Rathi writes the Zero newsletter, which examines the world’s race to cut planet-warming emissions. He is the author of Climate Capitalism.

Photograph: An employee works in the blast furnace at the Salzgitter AG mill in Salzgitter, Germany, on Tuesday, July 5, 2022. Salzgitter is looking to transform billowing foundries dating back decades into green steel production in a project to remain viable for years to come and a key test of German industry’s ability to transition to cleaner technologies. Photo credit: Krisztian Bocsi/Bloomberg

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Portugal Deadly Floods Force Evacuations, Collapse Main Highway

Portugal Deadly Floods Force Evacuations, Collapse Main Highway  Trump Demands $1 Billion From Harvard as Prolonged Standoff Appears to Deepen

Trump Demands $1 Billion From Harvard as Prolonged Standoff Appears to Deepen  AIG Underwriting Income Up 48% in Q4 on North America Commercial

AIG Underwriting Income Up 48% in Q4 on North America Commercial  AIG’s Zaffino: Outcomes From AI Use Went From ‘Aspirational’ to ‘Beyond Expectations’

AIG’s Zaffino: Outcomes From AI Use Went From ‘Aspirational’ to ‘Beyond Expectations’