It was 45 years ago today that a huge scaffold system collapsed inside a cooling tower under construction at a West Virginia power plant, sending 51 workers tumbling to their deaths 170 feet below.

Eleven members of one family were among the victims in the collapse, according to news reports at the time. None of the workers on the scaffold survived.

It’s been known as the worst and deadliest construction accident in U.S. history. Multiple lawsuits, workers’ compensation claims and liability settlements followed. The incident also led to fines against the contractors involved and resulted in significant changes in the way cooling towers are built and how projects are inspected by federal regulators.

“There were redundant features here that, if they had corrected them, this wouldn’t have happened,” Stan Elliott, who was the area director for the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, told the Charleston, West Virginia, newspaper in 2008. “If they had put the bolts in, it probably wouldn’t have happened. If they had let the concrete cure, it probably wouldn’t have happened.”

“But when you put all of these things together all on the same day at the same time, this is what happened,” he added.

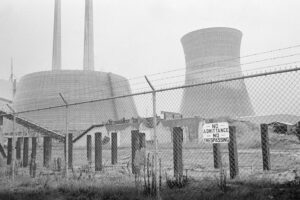

The coal-fired Pleasants Power Station, owned by Allegheny Power System, was under construction in 1978 at Willow Island, on the banks of the Ohio River, just 10 miles outside of Parkersburg, West Virginia. The first cooling tower had been completed the year before.

On the chilly morning of April 27, concrete workers, form carpenters and steel workers were on the scaffold system at the second tower, an elaborate, complex system that moved up as the tower rose in height. Sections of the scaffold had been bolted into concrete on the sloping wall of the cooling tower – concrete that had been poured just 20 hours earlier in near-freezing temperatures, according to a report filed a year later by accident investigators.

About 10 a.m., supports began to pull loose from the wall, quickly followed by more and more until the entire ribbon of concrete unspooled from the wall, witnesses and investigators said.

“The first thing I heard was concrete falling,” John Peppier, a worker on the ground, told the New York Times in 1978. “I looked over my left shoulder and I could see it falling. I could see people falling through the air and everything falling.”

“They just started dropping down like dominoes,” he said.

Other workers began digging through the steel and concrete debris. Fire departments from all around the region responded.

The National Bureau of Standards investigated the accident at the behest of OSHA. It found several problems that contributed to the collapse, including the fact that the wall concrete did not have the strength it needed for peak loads and had not had time to cure properly. The previous day’s pour of concrete was known as “lift 28.”

“It was concluded that the most probable cause of the collapse was due to the imposition of construction loads on the shell before the concrete of lift 28 had gained adequate strength to support these loads,” reads the 204-page report, available from the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

OSHA cited the contractors, including tower design-build firm Research-Cottrell Inc., for 10 safety violations and fined them $108,300. That was later reduced to $85,000. Research-Cottrell had pointed out that it had built 36 other cooling towers using the same system, without problems.

The general contractor, United Engineers and Constructors, hired its own consultant to study the causes. Lev Zetlin Associates found that workers did not fully understand the scaffold system, had been using it inappropriately, and were poorly supervised, according to the Charleston Gazette. The consultants also found that some anchor bolts had been removed too early.

A later report by OSHA also found issues with a cable, noting it was placed too close to the center of the tower, creating a greater load on the scaffold connectors, and that the scaffold and a crane had not been properly anchored to lower levels of the tower, The Constructor news site and the Times reported.

OSHA, criticized for having just seven safety inspectors in West Virginia at the time, adopted new regulations after the accident. Concrete must now be tested before formwork is removed or components are connected to it. A specialist must also review cooling tower plans and a detailed construction and safety plan must be developed ahead of time. Responsibility for formwork safety shifted from engineers to on-site contractors.

Reviews also found that formwork should not be tied together. A later accident at a cooling tower in Washington State killed two workers when a steel form pulled loose. It would have been much worse if the forms, like those at Willow Island, had been connected together, The Constructor reported.

Reports also noted that the workers at the West Virginia site were paid to work no more than eight hours a day, a potential incentive to rush the work.

Ralph Nader’s Public Citizen Health Research Group also said it found documents suggesting that OSHA had warned, before the accident, of disastrous consequences if the scaffolding was not used correctly. The memo was not followed up on, The Times reported.

The full extent of the insured losses and lawsuit damages from the Willow Island disaster are not clear. The West Virginia Department of Insurance had not provided information by late Wednesday. And workers’ compensation attorneys in Parkersburg and Charleston who may have handled some of the cases could not be reached.

A memorial to the lost workers stands nearby, at St. Mary, West Virginia. But the coal-burning power plant itself may not last much longer. It is set to close May 31, although the state’s utility commission is considering a plan to keep the plant open for another year. The plan would cost ratepayers about $36 million and would allow another utility company to study the feasibility of buying the facility, local news outlets have reported.

Top photo: The tangled mass that was the construction scaffold at the cooling tower on April 28, 1978. (AP Photo/Richard Greenawalt)

Topics USA Construction

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Markel Insurance Restructures Markel Specialty, Appoints Leaders

Markel Insurance Restructures Markel Specialty, Appoints Leaders  South Florida Insurance Broker Pleads Guilty to Fraud in $133M ACA Enrollment Scheme

South Florida Insurance Broker Pleads Guilty to Fraud in $133M ACA Enrollment Scheme  More Floridians Moving Out Due to Housing, Insurance Costs, Cotality Report Says

More Floridians Moving Out Due to Housing, Insurance Costs, Cotality Report Says  Allstate Agent Can Be Sued Over Nonrenewal of ‘Grandfathered’ Flood Insurance Policy

Allstate Agent Can Be Sued Over Nonrenewal of ‘Grandfathered’ Flood Insurance Policy