Two near-identical oil tankers trying to beat western sanctions. A secret transfer of Russian crude halfway between Iran and Oman. A supertanker giving a false location.

Welcome to the modern trade in Russian petroleum as western sanctions get tougher.

Earlier this month, the 1,089-foot supertanker Oxis collected about 1 million barrels of Russia’s flagship Urals crude from another vessel. The delivering ship was one of two owned and operated by Russia’s state tanker company Sovcomflot PJSC, according to TankerTrackers.com Inc, which specializes in detecting secretive cargo movements.

Definitively identifying which one, though, is tricky because the two candidate vessels share the same dimensions and are essentially indistinguishable from above. The maneuvers show how Russia can work around sanctions, and how challenging it will be to keep a permanent check on the flow of the nation’s oil if it makes increasing use of hidden cargo switches.

But the fact that Russian oil shippers feel the need to go to these lengths also suggests that buyers aren’t willing to openly defy US sanctions by accepting Russian cargoes delivered on sanctioned tankers. That will add to the cost of hauling barrels on those vessels.

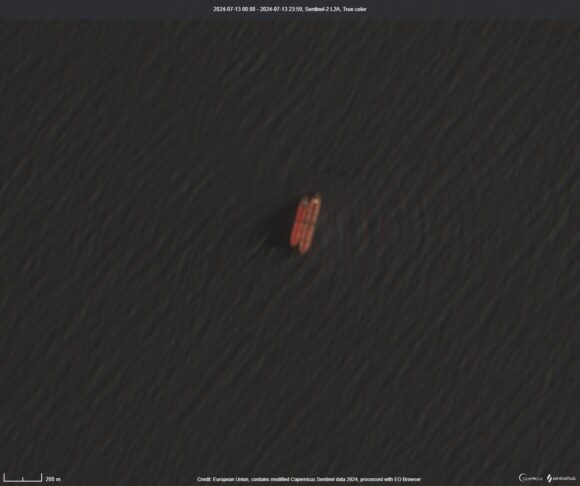

Sovcomflot tanker engaged in a ship to ship cargo transfer with the Oxis in the Gulf of Oman on July 13, 2024.

The two candidate tankers, both of which have been under sanctions from the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control since February, vanished from digital satellite tracking systems weeks ago.

The first, the Bratsk, loaded a cargo of about 1 million barrels of Urals crude at Russia’s Black Sea port of Novorossiysk in May, according to shipping information seen by Bloomberg. The second, the Belgorod, did the same thing in early June.

Both were then picked up by automated tracking systems as they left the Black Sea through Turkey’s Bosphorus shipping strait and were tracked on their voyages across the Indian Ocean to locations south of India, where automated tracking signals stopped.

The Bratsk, vanished from tracking on June 13, the Belgorod 11 days later.

Both have the same length and breadth, share the same reddish-orange deck color and have indistinguishable pipework. Importantly though, there are no vessels outside of the Sovcomflot fleet that share their characteristics, according to Samir Madani, founder of TankerTrackers.com.

The VLCC Oxis, is emitting a false automated position signal, showing it as being anchored in the Strait of Hormuz, close to Iran’s Jask oil terminal. However, satellite imagery shows no ship in its stipulated location and its reported latitude and longitude would imply that its transponder has moved by less than one meter between any pair of more than 1,400 signals in almost two weeks.

In reality, the Oxis was actually about 100 miles to the southeast, in the middle of the Gulf of Oman, when the cargo switch was made, satellite imagery shows.

The Belgorod reappeared on automated tracking systems on Tuesday, steaming along the southern coast of Oman toward the Red Sea having apparently unloaded cargo. There’s still no sign of the Bratsk.

The Oxis was sailing under the name Uzor until earlier this year and was identified by United Against Nuclear Iran as taking cargoes of Iranian crude by ship-to-ship transfer in October and December 2021.

Its commercial manager is a company called Umbra Navi Shipmanagement in Almaty, Kazakhstan, according to the international maritime safety database Equasis. Details of its insurance are not available on a database maintained for the International Maritime Organization.

No company called Umbra Navi Shipmanagement Ltd. was found on public registries run by the Kazakh government.

Most of the 53 tankers used by Russia that have been sanctioned by the US, the UK or the European Union since October have remained idle since being designated. About half of the 21 sanctioned Sovcomflot tankers have been renamed since being designated, another way of trying to distance the ships from the sanctions.

Moscow is now slowly starting to bring some of them back into use.

The first to load was the SCF Primorye in April. Its cargo was moved onto the Ocean Hermana in the Riau archipelago in early June. The oil may have been moved onto a third ship, according to TankerTrackers.com.

The Bratsk and the Belgorod are the only other two sanctioned ships to have been brought back into use so far. Sovcomflot declined to comment.

Both ships show as being covered against risks including oil spills by Moscow-based Sogaz Insurance, according to the company’s website. The company didn’t respond to a request for comment.

If their cargoes can successfully be delivered to buyers, most likely in China or India, without attracting the attention of sanctioning authorities, it may encourage Russia to make greater use of its sanctioned fleet.

But repeated ship to ship transfers will add to the delivery cost, eating into the profitability of the trade and reducing the benefits of putting the sanctioned vessels back into service.

Photograph: Sovcomflot tanker engaged in a ship-to ship cargo transfer with the Oxis in the Gulf of Oman on July 13, 2024.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Judge Awards Applied Systems Preliminary Injunction Against Comulate

Judge Awards Applied Systems Preliminary Injunction Against Comulate  Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears

Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears  Viewpoint: Runoff Specialists Have Evolved Into Key Strategic Partners for Insurers

Viewpoint: Runoff Specialists Have Evolved Into Key Strategic Partners for Insurers  World’s Growing Civil Unrest Has an Insurance Sting

World’s Growing Civil Unrest Has an Insurance Sting