The good news is that doctors are less likely to prescribe opioids to injured workers than they were years ago. They have come to recognize that the pain medications have been overprescribed, causing addictions and deaths including suicides.

The bad news is that the opioid crisis is not over by any means.

According to workers’ compensation medical experts, there is more work to do to make sure injured workers are receiving appropriate medical care. Many lives are still being lost. Opioid prescriptions are down but still popular. Also, they warn, some doctors maybe be turning to unproven alternatives or premature and risky surgeries in lieu of opioids.

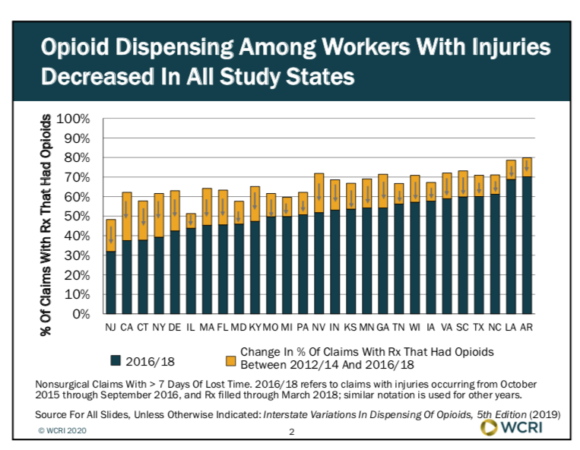

Studies from the Workers’ Compensation Research Institute confirm the trend away from opioids in workers’ compensation and toward alternative treatments. Vennela Thumula, a WCRI analyst and an expert on pharmaceuticals within the workers’ compensation system, shared the results of a 27 state study at this year’s WCRI Conference in Boston. The study looked at nonsurgical claims resulting in seven or more days away from work.

The study found that while opioids are being prescribed less, they are still somewhat prevalent. Opioids are still the most frequently used— in 10 of the 27 states WCRI studied. In the other 17 states, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most frequently prescribed pain medications.

The frequency and amount of opioids per workers’ compensation claim decreased between 2012-14 and 2016-18 in all 27 states studied. For example, the percentage of claims with an opioid prescription in California and New York fell from above 60% in 2012-14 to below 40% in 2016-18. Other states had similar results. Georgia and Nevada dropped 20 points to just above 50% during the same time period. Even Louisiana, where the percentage was as high as 80%, saw a 10 point drop.

According to WCRI, this downward trend has coincided with states enacting various reforms including prescription drug monitoring programs, drug formularies and limits on quantities that can be prescribed, as well as with the release of guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Shift to No Meds

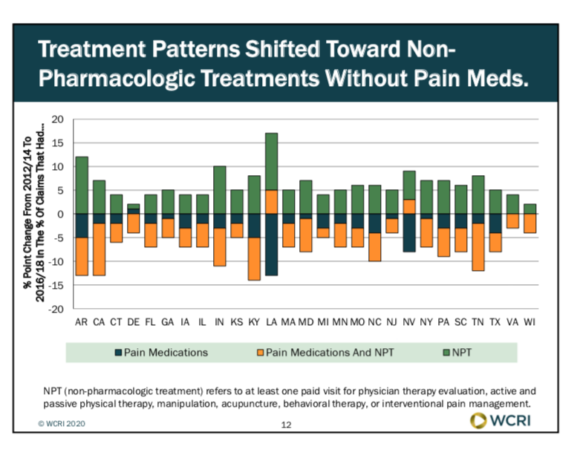

The study found doctors are increasingly prescribing other pain medications such as NSAIDs, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, topical analgesics, antidepressants, compound drugs, and other analgesics. While the popularity of opioid prescriptions was falling, the use of these non-opioid pain medications was increasing. However, non-opioid prescription use did not increase as much as opioid use decreased.

Something else was happening. By the end of the WCRI study period, there was a noticeable shift toward providing non-pharmacologic pain treatments. That is, more injured workers were receiving no pain medication at all.

The non-pharmacological treatments have included exercise, physical therapies, massage, and interventions such as injections and nerve blocks. There were also some reports of chiropractic sessions, acupuncture and behavioral treatments.

Back pain specialist Dr. Albert Rielly has seen what WCRI’s study shows about the drop in opioids as treatment. Rielly is an internist affiliated with Cambridge Health Alliance and Massachusetts General Hospital.

“Things have improved,” Rielly told the WCRI conference attendees, citing his own experience with patients. “I do see what the research is showing and there has been a lot less opioids prescribed for pain and a lot of other non-opioid pharmacological treatments.”

He recalled that the opioid epidemic had reached a point by 2009 where a study showed opioid overdose was the number one cause of death in workers’ compensation patients who underwent fusion surgery. “And now I’m pleasantly surprised that people are only getting NSAIDs,” he said, adding that he is “a big believer in exercise, physical therapy with active modalities along with NSAIDs.”

Selling on the Street

John Christian also has seen a drop in opioid prescriptions among the injured union workers served by his firm, Modern Assistance, an employee assistance program for the building trades in Massachusetts where he is chief executive officer.

“The good news is since we’ve been drug testing, we have seen a marked decrease in people testing positive and people coming to us for treatment because they are addicted to prescribed opioids. Big difference,” Christian told attendees.

However, Christian, who is also a substance abuse and mental health counselor, said his agency still sends from 15-30 people into medical detox every week.

Also, he is not seeing opioid deaths going down along with opioid use. “That’s the bad news of it,” he said. Why? Because it’s harder to get a prescription, more addicts are turning to the streets.

“What they’re telling us is because doctors are prescribing less there are fewer sold on the street, so they’re turning to what they used to think was heroin, and it’s not all fentanyl,” Christian said. “We’re seeing fewer prescription drugs on the street.”

He said his company does about 50 drug tests a month. Since most of its members are in safety sensitive positions, if a drug test comes back positive for an opioid, his firm tells the worker it needs to see a script. It then sends a narcotics control form with an Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) description of the workers’ job to the prescribing physician.

Nine times out of 10, because the prescribing physician has to sign on that form to say this person is safe, the forms are returned with something other than an opioid medication. “We see a lot of that,” Christian said.

Effectiveness of Alternatives

There is now more attention being paid to which opioid alternatives for pain management are being prescribed and which are effective, the experts agreed.

WCRI’s research shows a rise in the use of anti-convulsants and antidepressants, as well as nonpharmacological treatments such as chiropractic services and acupuncture. Also behavioral treatments are being prescribed for more workers.

Rielly said he thinks it’s sometimes difficult for a physician to tell a patent to go home and exercise or apply heat. The physician wants to give the patient experiencing pain something. “They want to leave with something, so they will give a prescription. I think it’s hard for them to step back and say, ‘What does the evidence show?'”

Some alternatives come with their own set of questions. For example, Rielly said there are differences in opinion around the timing of physical therapy for certain pain, whether to start in day one or wait.

“We’re still trying to find out how effective some of these treatments are, but also the timing as well,” he acknowledged.

Christian has seen an increase in alternative treatments including acupuncture, massage and cognitive behavioral therapies. “We’re trying to get people to not think about the pain, and not focus on the pain, which is a lot cheaper than sending somebody to detox or sending then to a ward,” he said.

‘Quick Fix’

Dr. Nina McIlree, vice president of medical management for Zurich North America, suggested that one problem is doctors who are “trying to fix the problem quickly and get onto the next one.” Why are they doing that? “Partly because the patient walking in wants the quick fix and to get moving. Some want to get back to work, and some just want a quick fix.”

What she has seen in the past five or six years is patients who were getting opioids to get back to work quickly are now getting NSAIDs as a pain treatment, as well as early physical therapy.

She cautioned the WCRI audience, however, about acupuncture. Her company has not seen great results with acupuncture and she thinks she knows why. “I don’t know that it is always used in the right application, the right diagnosis. Now, with the right diagnosis, absolutely it can help,” McIlree said.

McIlree also cited a spike in what she calls dermatologic treatments, or compounds, despite little evidence that they work. These compounds are like creams that typically sell for a dollar or less to which are added menthol similar to what is in Ben-Gay. “You put it in the cream. You might add a little bit of a nonsteroidal. It’s true cost, $40 bucks,” she estimated. But the charge to the insurer becomes more like $2,000, she said.

Some doctors have taken to packaging these in a kit with an athletic tape that patients can put across their elbows or across their shoulders. She said the ingredients these kits deliver are the same as what can be bought over the counter for a lot less. She said when her company questions a doctor or pharmacy on these kits, the prescription is withdrawn.

Invasive Therapies

McIlree also worries that there may be a trend of jumping too quickly to invasive therapies or surgeries such as implants of spinal cord stimulators or epidural steroid injections. While these can be effective, other treatments should be tried first, she emphasized.

She is concerned that doctors may be thinking since they can’t give the worker a pill, they’ll go right to surgery “as opposed to looking at what’s really the driver of this pain.”

McIlree said she understands that In order to move away from opioids, doctors may feel they need something for their patients but she says they should be offering alternatives that are safe and that work.

She acknowledged Christian’s concern that the pressure for a quick fix for a worker still exists because there are conditions that may not be part of the compensable injury but that are necessary to address to get the worker healthy and back to work

“How do you not focus on the pain? How do you focus on something that is more constructive to work towards?” she asked, suggesting that more cognitive behavioral therapies are needed.

Most important, she said professionals treating injured workers need to deliver the message that it’s not all about medications or therapies. “Really you get better when you engage in your own care,” she said.

Christian agreed with the need for workers to take some responsibility, for instance, in questioning a prescribing doctor, “What are you giving me? How long am I going to be on it? What are the side effects? Is it addictive? Is there an alternative?”

He tells his clients all the time, “You cannot depend on the doctor to know exactly what’s going on in your own life, with your body. So it’s up to you to ask those questions.”

Topics Workers' Compensation

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears

Insurance Broker Stocks Sink as AI App Sparks Disruption Fears  Munich Re Unit to Cut 1,000 Positions as AI Takes Over Jobs

Munich Re Unit to Cut 1,000 Positions as AI Takes Over Jobs  Preparing for an AI Native Future

Preparing for an AI Native Future  AIG’s Zaffino: Outcomes From AI Use Went From ‘Aspirational’ to ‘Beyond Expectations’

AIG’s Zaffino: Outcomes From AI Use Went From ‘Aspirational’ to ‘Beyond Expectations’