For Filicia Porter, the insurance bills were the final straw. They’d been climbing steeply for her assisted-living business as Florida was battered with ever more-powerful storms, and eventually, the numbers stopped adding up.

So in March, she finally decided to call it quits, shutting the facility near Palm Beach that she opened just two years ago. That came four months after she closed an older location in Port St. Lucie, opened in 2017. Together, they left a dozen residents scrambling to find another place to live.

“Each year you see a rise. Why pay more?” said Porter, who first started The House of Cares to capitalize on the burgeoning demand for elder care as baby boomers flooded into the Sunshine State. But now, as her premiums soared on top of all her other costs, she just couldn’t “continue to deplete” herself.

Porter is just one small example among many in Florida, where two major, generational forces are colliding: The toll of climate change, and the challenge of caring for an aging society. Drawn to the state’s warm weather and low taxes, baby boomers have been piling into the retirement haven for years, leaving it with one of the most elderly populations in the US. That’s turning it into a harbinger for other states as the consequences of rising temperatures ripple through the economy in ways few had envisioned.

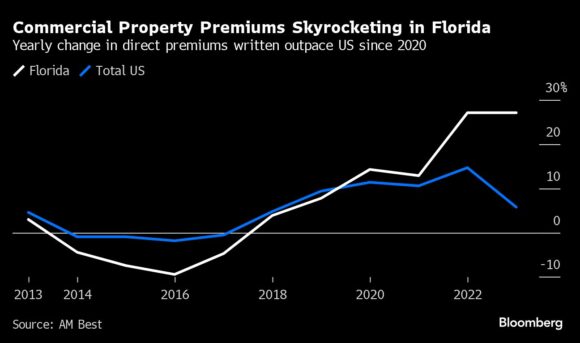

With Florida being threatened by more powerful hurricanes, commercial-property insurance costs last year surged at nearly five times the national pace, according to credit rating firm AM Best Co. Inc. That’s slapping what care providers say is effectively a new — if little noticed — tax on an industry already contending with labor shortages, soaring wages and rising supply costs.

The result? More and more nursing homes are closing down each year, while others are missing debt payments. At the same time, the costs for senior care – at all levels from independent living to around-the-clock nursing — are rising, threatening to become unaffordable for a growing number of retirees.

“We are headed into a train wreck,” said Pilar Carvajal, founder and CEO of Innovation Senior Living, a Winter Park-based operator with 339 residents at its facilities, which offer services including memory care and assisted living. Its insurance costs jumped at least 50% in the past five years. “We need help to solve this societal problem,” she said.

While climate change has pushed commercial-property insurance premiums up nationwide, few places have been hit harder than Florida. In the five-year period ending 2023, costs surged 125%. Last year, annual premiums soared about 27% in the state — for the second year in a row — while nationwide the growth rate slowed to nearly 6% from about 15%, according to AM Best.

“We have many clients that can’t afford the coverage,” said Patrick McConachie, senior vice president at Marsh McLennan Agency in Tampa, who helps senior-living operators negotiate policies. “In a lot of cases in Florida recently, the operator will simply turn the keys back over to the landlord.”

Read more: There’s a New Financial Crisis Brewing in Uninsurable US Homes

Palm Garden Healthcare shuttered its assisted-living facility earlier this year because of skyrocketing costs, said President and CEO Rob Greene. The property insurance bill for his 14-location nursing home chain more than doubled in two years to $2.2 million. And although Greene is paying more to be insured, he said the coverage for $75 million in damages is far below the at least $200 million he needs.

So far, Palm Garden hasn’t experienced any major storm damage since it opened for business in the late 1980s, but “come June, we get a little bit nervous,” Greene said.

‘Feeling The Pinch’

From 2019 to 2023, damage from natural disasters like tropical cyclones and severe storms at least doubled to as much as $200 billion from the 10 years prior, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information. That five-year tally includes Hurricane Ian — the third-costliest hurricane in US history.

The mounting claims led a few property insurers to fold, driving up rates. But this year, seven new firms are expected to enter the market, according to Mark Friedlander, director of corporate communications at the Insurance Information Institute. And negotiations with reinsurers went well, which could mean flat or smaller premium increases this year, said Jack Walker, senior sales executive at AssuredPartners, an Orlando-based insurer specializing in senior living.

However, until that happens, operators like Innovation and Palm Garden have to find ways to pay the ballooning bills. Palm Garden’s elders qualify for Medicaid, but the reimbursements are never enough, according to Greene. “We don’t have the luxury of like, a McDonald’s, of being able to pass on costs,” he said.

For operators serving more affluent retirees that can raise and pass the price on, even they will at some point become “unaffordable,” said Margaret Johnson, senior director at Fitch Ratings.

“Residents are feeling the pinch,” said Raoul Nowitz, senior managing director at SOLIC Capital Advisors, who specializes in restructuring for distressed companies and investment banking. And operators are struggling to have enough cash flow to cover debt, he added.

While the spike in insurance costs is a major problem for all groups in Florida — from homeowners to hotels — it’s particularly crippling for this industry. Fitch’s Johnson has a negative credit outlook on the sector.

When he speaks with chief financial officers of Florida senior-living communities, labor and property-insurance costs are “at the top of the list of things that keep them up at night,” said Richard Scanlon, senior managing director at B.C. Ziegler and Company.

A majority of first-time payment defaults on debt issued for Florida retirement communities since 2009 took place after the pandemic — 21 out of 34 — according to Municipal Market Analytics. The default rate for senior living in Florida stands at 18% — more than twice the nearly 8% national rate, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Read more: More Defaults for Senior Living Ahead as Debt Comes Due

Supply and Demand

That strain has been causing dozens of facilities to shutter. In the five years ending 2023, an average of 146 nursing homes or assisted-living facilities have closed each year, according to data from the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration. Within that period, 2022 saw the most closures — coinciding with Hurricane Ian’s landfall along with the winddown of federal pandemic aid.

The steady closures occur as demand grows and prospects of new facilities dim. Florida is the nation’s second fastest-growing state based on population behind Texas, according to the US Census Bureau, and ranks second among US states for its elders, with about 22% aged 65 and over, compared to just 17% for the entire US.

New facilities have to open at a faster rate to keep up with the expanding demographic, said Lisa Washburn, chief credit officer at Municipal Market Analytics, adding that “construction has slowed significantly” across the US. There needs to be some sort of governmental involvement to subsidize or facilitate building, she said.

“In Florida you may not have an income tax,” but insurance is a tax, said Washburn.

Following Hurricane Ian, Carvajal had to install a $200,000 new roof on one of her six facilities to continue to be insured.

“How do you make it work when things like property insurance just are becoming so onerous and unpredictable?” she said. “Looking into the future, if things are going to get worse, I don’t know what we’re going to do.”

Written by Lauren Coleman-Lochner and Melina Chalkia, Bloomberg

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

Florida Engineers: Winds Under 110 mph Simply Do Not Damage Concrete Tiles

Florida Engineers: Winds Under 110 mph Simply Do Not Damage Concrete Tiles  Nine-Month 2025 Results Show P/C Underwriting Gain Skyrocketed

Nine-Month 2025 Results Show P/C Underwriting Gain Skyrocketed  What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market

What Analysts Are Saying About the 2026 P/C Insurance Market  A 10-Year Wait for Autonomous Vehicles to Impact Insurers, Says Fitch

A 10-Year Wait for Autonomous Vehicles to Impact Insurers, Says Fitch