It doesn’t matter if the earth sways in Chile, Alaska or Japan, the formation of the sea floor along the U.S. West Coast generally aims any tsunami surges at the tiny California port town of Crescent City. Churning water rushes into the boat basin and then rushes out, lifting docks off their pilings, tearing boats loose and leaving the city’s main economic engine looking as if it has been bombed.

That’s what happened in March 2011, when a Japanese earthquake sparked a tsunami that sank 11 boats, damaged 47 others and destroyed two-thirds of the harbor’s docks.

Port officials are hoping that tsunami is among the last of many that have forced major repairs in Crescent City, a tiny commercial fishing village on California’s rugged northern coast. Officials are spending $54 million to build the West Coast’s first harbor able to withstand the kind of tsunami expected to hit once every 50 years – the same kind that hit in 2011, when the highest surge in the boat basin measured 8.1 feet (2.5 meters) and currents were estimated at 22 feet (6.7 meters) per second.

Officials are building 244 new steel pilings that will be 30 inches (76 centimeters) in diameter and 70 feet (21 meters) long. Thirty feet (9 meters) or more will be sunk into bedrock. The dock nearest the entrance will be 16 feet (5 meters) long and 8 feet (2.4 meters) deep to dampen incoming waves. The pilings will extend 18 feet (5.5 meters) above the water so that surges 7 1/2 feet (2.3 meters) up and 7 1/2 feet down will not rip docks loose.

Crescent City was not the only West Coast port slammed by the tsunami, which was generated by a magnitude-9.0 earthquake in Japan. The waves ripped apart docks and sank boats in Santa Cruz, California, and did similar damage in Brookings, Oregon, just north of Crescent City. But their geographical location doesn’t make them as vulnerable to multiple tsunamis.

“Normally, Crescent City takes the hit for all of us,” said Brookings harbormaster Ted Fitzgerald.

Since a tidal gauge was installed in the boat basin in 1934, this small port has been hit by 34 tsunamis, large and small. It typically suffers the most damage and the highest waves on the West Coast, said Lori Dengler, professor of geology at Humboldt State University.

The sea floor funnels surges into the mouth of Crescent City’s harbor, and the harbor’s configuration magnifies them, experts say.

A wave generated by an earthquake in Alaska on Good Friday, 1964, killed 11 people and wiped out 29 city blocks. That was 10 years before the boat basin was even built.

When the waves hit in 2011, the port was still repairing damages from a tsunami that hit in 2006. Officials already had a plan for dealing with future tsunamis, said Ward Stover, owner of Stover Engineering in Crescent City, which put together the plan.

With no tsunami building codes, Stover said the state of California and Crescent City decided to prepare for the kind of tsunami expected to hit every 50 years. They rejected as too expensive building a tidal gate to close off the mouth of the harbor or trying to survive a powerful tsunami like the one that hit in 1964. Instead, they planned to make the docks strong enough to ride out the most likely surges.

“It’s tsunami-resistant, not tsunami-proof,” Stover said.

Construction has been marked by one delay after another. Government funding was slow, and a custom-built drill bit for installing the extra-strength pilings deep in bedrock broke. So authorities switched to installing temporary docks the old-fashioned way, by pounding in the pilings, to get them through the winter. Many of the 60 commercial fishing boats based in Crescent City are still mooring in the outer harbor. Others have to make do without water or electricity.

The March 2011 tsunami was a wake-up call for communities up and down the West Coast. Many improved tsunami evacuation plans and held mock evacuations.

But some experts say the West Coast is still not taking the threat seriously enough.

“Many ports on the West Coast are in denial as to their tsunami hazard,” said Costas Synolakis, professor of civil and environmental engineering and director of the Tsunami Research Center at the University of Southern California.

Was this article valuable?

Here are more articles you may enjoy.

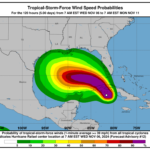

Florida’s Citizens Suspends Binding on Policies as Another Storm Churns in the Gulf

Florida’s Citizens Suspends Binding on Policies as Another Storm Churns in the Gulf  NFIP to Begin Taking Monthly Flood Insurance Payments

NFIP to Begin Taking Monthly Flood Insurance Payments  How Trump’s Second Administration Affects Business: Musk, Tariffs and More

How Trump’s Second Administration Affects Business: Musk, Tariffs and More  Boeing Dismantles DEI Team as Pressure Builds on New CEO

Boeing Dismantles DEI Team as Pressure Builds on New CEO